Natural Resources at He‘eia Bay

He‘eia is not a destination beach for people who love long stretches of soft sand. It’s one of the rockiest beaches in the area, yet one filled with precious natural resources — animal, mineral and vegetable.

Rocks

Lava

Āʻā lava (the bumpy kind that looks like a landscape of broken up rocks) covers most of the area, and can be seen underneath the vines that have grown over it. The giant cinder cone close to the beach is a direct result of volcanic activity. Lava has been here for hundreds of thousands of years, but all things sitting on it have not.

White coral

White coral is often mistaken for rock, but each piece was once a whole living colony of sea creatures that have died and been washed up on the beach.

‘Ili ‘ili

‘Ili ‘ili is the Hawaiian name for the small black pebbles that are found on the south end of the beach. They were sometimes hand-pounded into the ground, to create a floor, or platform, most often for a dwelling. An example of a possible platform for a dwelling can be seen on the mauka (mountain) side of the footpath to the beach.

Granite

Granite is the heavy, dark bedrock scattered among the lighter weight, lava rocks. We have hand-set medium sized granite rocks to form a solid foundation under wood chip mulch to create the wheelchair accessible path to the beach.

The ocean bay

Mammals, reptiles, mollusks and fish

Because of its isolation, He‘eia Bay is cleaner than most other bays on the Kona Coast. It is the home of many sea creatures, though not as many as 20 years ago. Since 2016, we have seen spinner dolphins (naiʻa) at the mouth of the bay, green sea turtles (honu), especially near the rock outcropping on the north side of the bay, some invertebrates, including a few squid, sea slugs, lots of snails, and an abundance of fish. Among the fish we have identified by matching what we see to pictures in the book, Hawaiian Reef Fishes are: spotted box fish (moa) lots of kinds of butterfly fish (kīkākapu), many yellow ones and occasionally a long nose black one, chubs (nenue) damselfish, especially Hawaiian Sergeant (mamo), eels, silvery flagtails (āholehole), goatfish of various colors, groupers (pilikoʻa), hawkfish, jacks (‘ulua), moorish idols (kihikihi), mullets, needlefish, parrottfishes of various colors (uhu), puffers (o‘opu), manta rays (hāhālua), spotted eagle rays (hailepo), a grey reef shark (manō), surgeon fish, especially yellow tang (lauʻīpala), and convict tang (manini), trigger fish (especially black ones,humuhumu ‘ele‘ele), trumpet fish (nūnū) cornet fish (nūnū) and many kinds of wrasses (hinalea).

Living Coral

Coral may seem like plants in the ocean, but they are actually groups of small animals whose skeletons join together to form a variety of shapes, sizes and colors. They do have single-celled plants living inside them, called zooxanthellae, that provide much of the food they eat and color that you see. Several kinds of coral can be seen in He‘eia Bay. They are in better shape than the heavily used Kahalu‘u Beach, though they are outshone by the dramatic coral canyons just south of the mouth of the Bay. Like all over Hawai‘i, the recent trend of climate change and ocean warming has stressed the coral in He‘eia Bay resulting in bleaching during warmer months and some dying off of some colonies. At one point in late 2015, it almost looked like a Mexican celebration of Day of the Dead. Fortunately, some of the coral has come back and others were more resilient to begin with. We will be working with local researchers to identify the specific species of coral in He‘eia Bay and to document changes over time.

Unique brackish pool

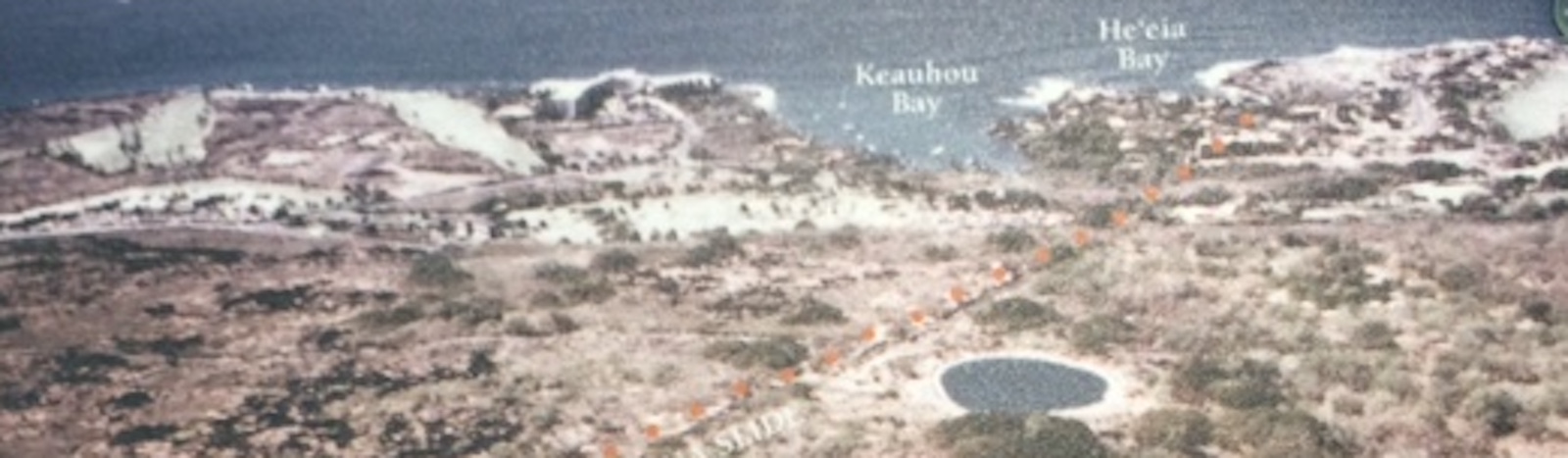

He‘eia Bay is the site of an ancient brackish pool that was filled in with rocks swept in by the 2011 Japanese tsunami and covered up with overgrowth until we re-discovered it in 2016. Some archaeologists think this may have been a bathing pool for the royalty, who had their residences at Keauhou Bay, but used He‘eia Bay as a playground for surf and sledding (hōlua). Now called anchialine pools, brackish pools in lava rock are not unique to the Big Island, but they are not found in this concentration anywhere else on Earth. Fresh water comes from the mountain through underground tunnels and porous basalt lava rocks. Salt water comes from the ocean through underground tunnels and cracks, creating a brackish mix that fluctuates with the tide, and a perfect habitat for a teeny tiny intensely red shrimp found only in Hawai‘i. These shrimp have been rapidly disappearing due to the invasion of guppies and tilapia, but they are not yet endangered. The habitat that supports them is what’s in jeopardy throughout West Hawai‘i. Many anchialine pools have been lost through development on the Kona – Kohala Coast, especially up north. Hawaiʻi Wildlife Fund and others have begun the work of protecting this rare habitat. We are happy to have their support in our efforts to restore this precious resource to its original state.

Fresh water

For a long time, there were two, freshwater wells near the large cinder cone by the beach. Before 1930, families on the Kanaloa bluff as well as a couple of homes right in He‘eia Bay used it for drinking water. However the kiawe (mesquite) and opiuma (Fabacea) trees and other invasive vegetation in the area are water hogs and soon depleted the fresh water. For awhile the wells still, held brackish water, used for cleaning. Now they are covered over. We will try to mark the wells.

Trees, bushes, plants

Well before the first Polynesians arrived, tree seeds carried by birds or wind fell into little fissures in the lava, took root, broke through lava and eventually became little forests. A small proportion of these were endemic, meaning they took root only in Hawai‘i and nowhere else on Earth. Others were also carried by wind, wing or water to other places, so are native plants both here and there. The earliest Hawaiians heavily used not only the wood, but also the leaves and fruits from these trees. Overtime they depleted the forests closest to shore. So 800 years ago there may have been natural dry forests at He‘eia Bay, but it is unlikely there were still many trees by the mid 1700s when Europeans arrived.

Kiawe Trees

Within the last 250 years, some of the land in Hawai‘i has been deliberately replanted with species carried by humans from across the seas. For example, in 1828 a Catholic Missionary carried kiawe (pronounced key- ah- vay) seeds from a garden in Paris (from a tree that originally came from Peru – a variation of the mesquite) and planted them in Honolulu. 189 years later these massive thorny trees are on the land surrounding He‘eia Bay and up and down the Kona coast.

Some say the wholesale planting of kiawe trees was the work of missionaries, who thought the fierce thorns would convince native Hawaiians to wear shoes. Other cite their commercial value, as excellent cattle feed. Today kiawe is recognized as one of the best possible woods for underground cooking and keeping a barbecue fire going.

While parts of the leeward coast are covered with kiawe trees, there are fewer today at He‘eia Bay, than there were in 2011. The 2011 tsunami, triggered by a 9.1 magnitude earthquake off of Japan, uprooted several of the giant trees, pulling some out to sea, and leaving some giant roots behind. The bottom trunk of a giant uprooted tree from an earlier tsunami remains on the land and has become a classic subject for photographers, as seen on this page. We will not remove any of these historically important trees, but because they were not here originally, and their huge thorns undercut their value as shade trees, we will not plant any more of them.

Other trees we will care for

Besides kiawe, some trees that we will maintain and care for at He‘eia Bay include: the fragrant tamarind (whose pods sweeten as they ripen and dry out; they’re eaten like candy by local people); kao (one of the few native trees, a source of shade, seen along the walking path); noni (brought by the first Polynesians for its medicinal properties, and otherwise used only as a “famine food,” because of the stinky nature of the fruit); the autograph tree (whose cardboard-like leaves, became a way for writers to go paperless, long before technology); and flowering plumeria (not native to our island, but said to be one of the first plants brought here by the Polynesians).

Which ones we’ll remove

Two trees we won’t keep and support are haole koa and ‘opiuma. Haole is the word for a foreigner, and some naturalists have called haole koa an “alien pest” for good reason: It spreads fast, chokes out native plants, and is hard to get rid of. For years it had completely covered the pebble platforms and lava walls that are now visible, and provided cover for folks to engage in illegal activity, including drug dealing. It’s definitely not in the same family as the wonderful true koa that is endemic to Hawai‘i. (endemic means it only grows here.) Another invasive tree we are trying to clear out is ‘opiuma. Basically, it’s all thorns with no redeeming value and it’s leaflitter is rich in nitrogen which will change the soil chemistry (same with kiawe and haole koa). Keeping He‘eia Bay clear of these invaders so native species have a chance to grow is one of our most challenging ongoing projects.

Plants and bushes

Much of the land around He‘eia Bay is covered with beach naupaka, an indigenous plant, which also grows in other ocean environments around the world. We like it. It has three things to recommend it: A unique flower that looks like half is missing; “button” fruit that can be squeezed and used for refreshing eyedrops; and a defogging property that is activated by crushing the leaves and wiping goggles with them. The legend behind this unusual flower is that in olden times a royal princess fell in love with a commoner. Despite their great love, they were never allowed to marry. All of nature shared her grief, and the naupaka responded by missing half of its flowers for the rest of time. A plant that is spreading rapidly on the north wall along the bottom of the paved alley is the night blooming cereus. It has dramatic, ornamental flowers, but they close up during the day, and the plant is very thorny.

A terribly invasive, though native vine that can and does grow across rocky environments is a type of morning glory, called pōhuehue. We are still trying to figure out how best to relate to it. For now, we are trying to remove it from places where it is choking out plants we want, like naupaka, and where it covers distinctive large rock outcroppings, and keep it trimmed as a ground cover on much of the rest of the space.

A weed that we’re not ambivalent about is the detested lantana, often called Hawaii’s “quintessential” weed. It has taken root in several places and continues to be sold at box stores and nurseries as it’s flowers are decorative. We have cut it down, but it needs to be dug up by the roots, and it’s thorns are painful. This weed is common throughout the coast along Hawai‘i Island and is now being spread by birds.

We need to add the description of other plants

Animal life

Reptiles

We’ve seen two kinds of geckos: little black ones with white spots, and the big green invader geckos, called Madagascar day geckos, that, cute as they are, prey upon the little ones (note: there are no native geckos, just the ones that came first). We have also seen Jackson chameleons: those are cute but not native either

Birds

Have seen fat pheasants, but they are not native, and it’s an area usually visited by kolea – Pacific Golden Plovers, and auku’u – black crowned night heron, and ‘ulili (Wandering tattlers)…. Will have to keep an eye/ear out Rose and Kay can you add to this?) W

References

Local people (including our Board members)

Archaeological documents

A bunch of Books (bibliography being compiled)

Wikipedia

Kamehameha Schools Bishops Estate website

https://apps.ksbe.edu/kaiwakiloumoku/kaleinamanu/he-aloha-moku-o-keawe/aiaiheeia